House, M.D. was a U.S. television show from 2004 through 2012. The show’s main character, Dr. Gregory House, was (according to Wikipedia) “a pain medication-dependent, unconventional, misanthropic medical genius who leads a team of diagnosticians at the fictional Princeton–Plainsboro Teaching Hospital (PPTH) in New Jersey.” One of his recurring mantras that frequently worked its way into episode plot lines was that “everybody lies.” His colleagues would frequently discount his diagnoses based on statements from the patients. He consistently insisted that they were always lying and, of course, he was always right.

I’ve never been a big fan of focus groups or consumer surveys. There are several reasons to be highly skeptical of such things. It may be a bit hyperbolic, but taken collectively one would be forgiven for thinking that “everybody lies,” including your prospects.

Let’s Pick on Millennials

Not because they necessarily deserve it, but because the marketing world seems to be obsessed with them at the moment. Major brands are betting their futures based on consumer surveys of millennials by changing their business practices and even their product offerings. The logic here is that this generation is where the growth will be. They’re just starting to enter the years when they’ll be buying homes and starting families. So far, this makes a whole lot of sense. But there’s one major flaw that’s starting to pop up.

They’re lying.

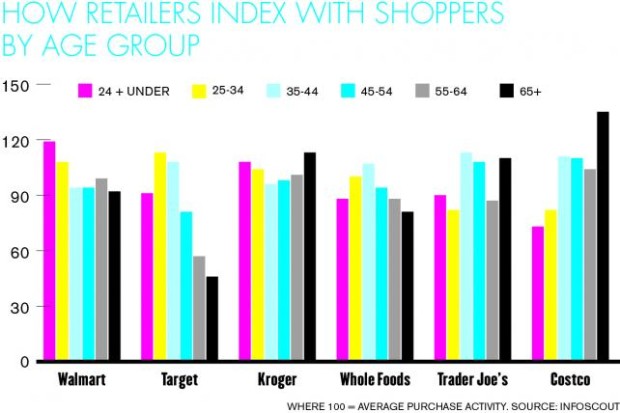

I’ve read several articles recently that provide evidence indicating that some of these major brands have based their decisions on flawed surveys. The first such example is that Millennials apparently love Wal-Mart — and employees are shocked. Why are they shocked? Because most retail analysts insist that millennials prefer smaller, more intimate shopping experiences over the big-box stores. At least that’s what they say when asked in consumer surveys. But their behavior contradicts this assumption. “Millennials now, as a generation, like Walmart the best, more so than Generation X, more so than boomers,” Matt Kistler, Walmart senior VP-consumer insights and analytics, told Ad Age.

While Walmart is pleasantly surprised that millennials are lying in market surveys, McDonalds may not be lovin’ it so much. Neither are Pizza Hut or Olive Garden, all of whom have revamped their menus to better appeal to millennials. They want to attract these younger consumers, hoping that they will become life-long patrons. According to a recent article on Business Insider, millennials are lying about what they want to eat, and it’s destroying fast food.

To appeal to millennials, McDonald’s overloaded its menu with premium smoothies, gourmet sandwiches, and creative salads. Pizza Hut added a variety of customizable options including fresh spinach and Sriracha drizzles. And Olive Garden released a tapas menu of gourmet-style small plates to attract the foodie generation.

All of these efforts flopped, and there’s an important reason: Millennials are lying about their food habits. Millennials say they want food that is high quality, free of additives, and sustainable, but they aren’t always willing or able to pay for it.

The only reason I’m picking on millennials is that there has been a recent slew of articles about how marketing assumptions about them are proving to be very different from their actual behavior. But I work predominately in the B2B space – particularly with engineers – and deal with the exact same disconnects between perception and reality. As marketers, we need to be extremely cautious about relying on what people tell us they want.

Let’s take a look at some reasons why people’s behaviors don’t always match their self-professed values.

Our Brains Lie to Us

Sometimes the fact that we’re not telling truth isn’t entirely our fault. It turns out that our brains lie to us all the time. One of the developments that’s causing scientists to explore the fallibility of our memories is the alarming number of criminal convictions being overturned by DNA evidence. In a whopping 75% of those cases, the primary evidence was eyewitness testimony.

So why do humans make such terrible witnesses? One reason is that our memories are much lower resolution than we think. When we recall a memory, it seems extremely vivid to us, but that’s because the brain hates fuzzy memories and so it interpolates and substitutes details it thinks belong there but weren’t necessarily. There are two sources for these interpolated details: pre-existing schemas and other memories. We understand the world through our own stereotyped models of the world, and so when details are lacking we fill them in with assumptions from our schema library. Most of the time, we’re not even conscious of the fact that we do it. Other times, our brains simply conflate memories and borrow details from one event to fill in the gaps in another.

There are many other reasons why our memories fail us. For a more complete list, read Eyewitness Memory Is Unreliable by human factors expert Marc Green.

We Are Irrational

Many theories and strategies rely on the assumption that people will act rationally in their own self-interest. While the latter is probably true in most cases, the former is demonstrably false. The truth is that we humans are not nearly as rational in our decision-making as we like to think.

In his book Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely says “When we believe beforehand that something will be good, it generally will be good – and when we think it will be bad, it will be bad.” This was his conclusion following a series of experiments on the effect of expectations. In one experiement, he offered free beer to MIT students. He offered them two flavors, one of which was regular Budweiser and the other was Budweiser with two drops of balsamic vinegar. One group of students was given the samples without any introduction. This group showed a strong preference for the beer + vinegar combination. However, when the second group was told before tasting that the second beer had vinegar added to it, they much preferred the plain version.

In a similar experiment, Ariely offered students free coffee. Over a series of days, he switched up the containers that held the condiments. For one group, they used beautiful glass-and-metal containers on fancy brushed metal trays. Another group was given styrofoam cups with hand-written labels in a red felt pen. The students who were given the condiments using the fancy serving ware gave much higher ratings for the coffee’s flavor than those who were served using the styrofoam cups.

There are countless other examples in his book that shoot down the notion that we always make rational decisions. This is another big reason why the things we say don’t always match the things we do.

We Simply Don’t Know

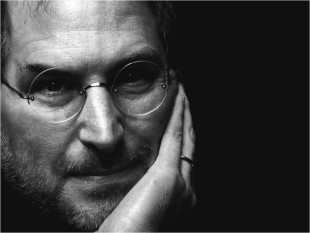

Asking customers what they want can be a tricky strategy. Henry Ford if frequently credited with saying, “If I had asked my customers what they wanted they would have said a faster horse.” While the evidence as to whether or not he actually uttered these words is sketchy, his actions certainly support the sentiment. However, there is one famous innovator who expressed a similar philosophy much more recently. Steve Jobs famously said, “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

I’ve had my own experience with this concept as well. My first job out of college was as an automation engineer and my job was to use technology to make manufacturing equipment faster, more efficient, and higher quality. The machine operators were invaluable to my designs, because they knew things intuitively that we engineers could never, ever calculate. However, I quickly learned that it didn’t work very well when I asked them, for example, what they would like a user interface screen to look like. It didn’t work because they simply didn’t know what was possible. The best outcomes happened when I asked them what the pain points were, showed them possible solutions, and then incorporated their feedback into the final design.

Conclusion

We’ve seen hard evidence that customers lie to marketers and covered a small fraction of the reasons why this happens. Now, I am not saying that customer surveys and market research are useless. I’m saying that they are fallible. My own philosophy as a marketer is, “Trust but verify.” I’ll use customer sentiment and surveys as inputs to designed experiments that test the veracity of the assumptions before making game-changing strategic decisions.

Because everybody lies.